Lab 5: Interrupts

Introduction

This is the second Lab in E155 working with microcontrollers. The goal of this lab is to get comfortable with interrupts through designing an algorithm to sense quadrature encoder pulses and convert these into motor velocity and direction.

Design and Testing Methodology

The primary challenges of this lab are in the setup of the interrupts themselves. There are 4 possible interrupts, a rising or falling edge at A, or a rising or falling edge at B. This gives us all the information we need to be able to determine both velocity and direction.

Interrupt Based Code vs Polling Based Code

Interrupts are better than manual polling because they allow the microcontroller to respond immediately to encoder signal changes without constantly checking pin states in a loop. This makes the system far more efficient, as the CPU can perform other tasks while waiting for events instead of wasting cycles on continuous polling. At high speeds, interrupts also ensure more accurate and reliable pulse detection, since polling may miss transitions that occur faster than the loop’s execution rate.

To have correct data, we need to satisfy the Shannon-Nyquist theorem that \(f_{sample} \geq 2 * f_{max}\). For manual polling, we need to pick a sampling rate and if the frequency of the motor hits a certain threshold then we will have aliasing, where it will read a lower frequency.

Interrupt servicing is almost always much faster than polling loops, meaning that we can detect a much higher max frequency before aliasing or any other issues arise.

To test this, I created 2 different versions of my code, one with manual polling and one with interrupt based polling. Our power supplies go up to 20 V, and the motors can only handle around up to 24 V according to the data sheet, so 20 V is the maximum voltage I ran them at. At this speed, I was getting around 5 RPM. For both the polling and interrupt methods, this was a low enough speed that they were missing no edges, and thus no alliasing was observed. Eventually, the polling will hit it’s threshold before interrupts, but for a low speed application like this both are completely accaptable.

Frequency Generator Tests

Because the motor only goes up to around 5 RPM, we were not able to reach the threshold for aliasing either the interrupt or polling based methods. To push artificially higher loads, I used a square wave function generator set to 50% duty cycle, to simulate one of the quadrature encoder pins toggling.

For this testing, I grounded one of the typical pins, and only used one of the pins (so we do not have direction data, but can test max frequency). I adjusted the frequency formulas to account for half as many interrupts / edges. Therefore, we are strictly measuring how fast the interrupts can measure edges vs how fast the polling method can detect a change in the pin value. For both of these methods, I kept the the calculations and printouts to be fair. Thus, it is not the fastest possible interrupt or the fastest possible polling (as I could make the ISR or the polling loop shorter), but it is a reasonable test for interrupts and polling in a real application such as this.

Function Generator Testing Note:

Note, because I am using only one pin, this frequency will represent double the max RPM readable using the motor, as only one pin is toggling instead of two. With two pins, we get twice the interrupts, and we will start getting issues at half the rate. Thus, for this testing, the printed frequency is DOUBLE what we could achieve with a motor.

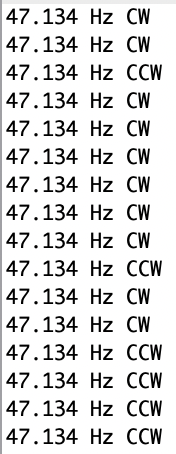

Figure 1 shows a steady output of 47.13 Hz. There is no aliasing present. This is the maximum frequnecy that I could get a stable reading at, above this some slight aliasing occured, with the effect getting worse as I increased frequency.

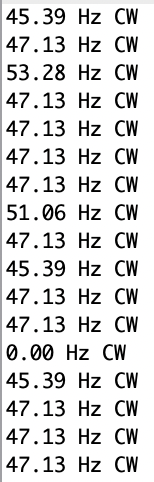

Here, I used my polling based method, but at the maximum frequency that I used for the polling based method. Here we see very severe aliasing, and we have unusable data. We still see a majority of datapoints showing the correct value, but we have some higher and some lower, and lots of noise.

The polling based method stopped being stable around 12 KHz on the function generator. This explains why we did not see any issues with the motor at 20V, as this is equivalent to the motor at 14 RPM, which is way more than the ~5 RPM of the motor. If the motor was above 14 RPM, we would see issues with the polling method but not the interrupt method (up to a point).

In conclusion, I would be able to detect a motor moving to around 23 RPM using the interrupt based method without having any aliasing effects, but would start having problems at 14 RPM using the polling based method.

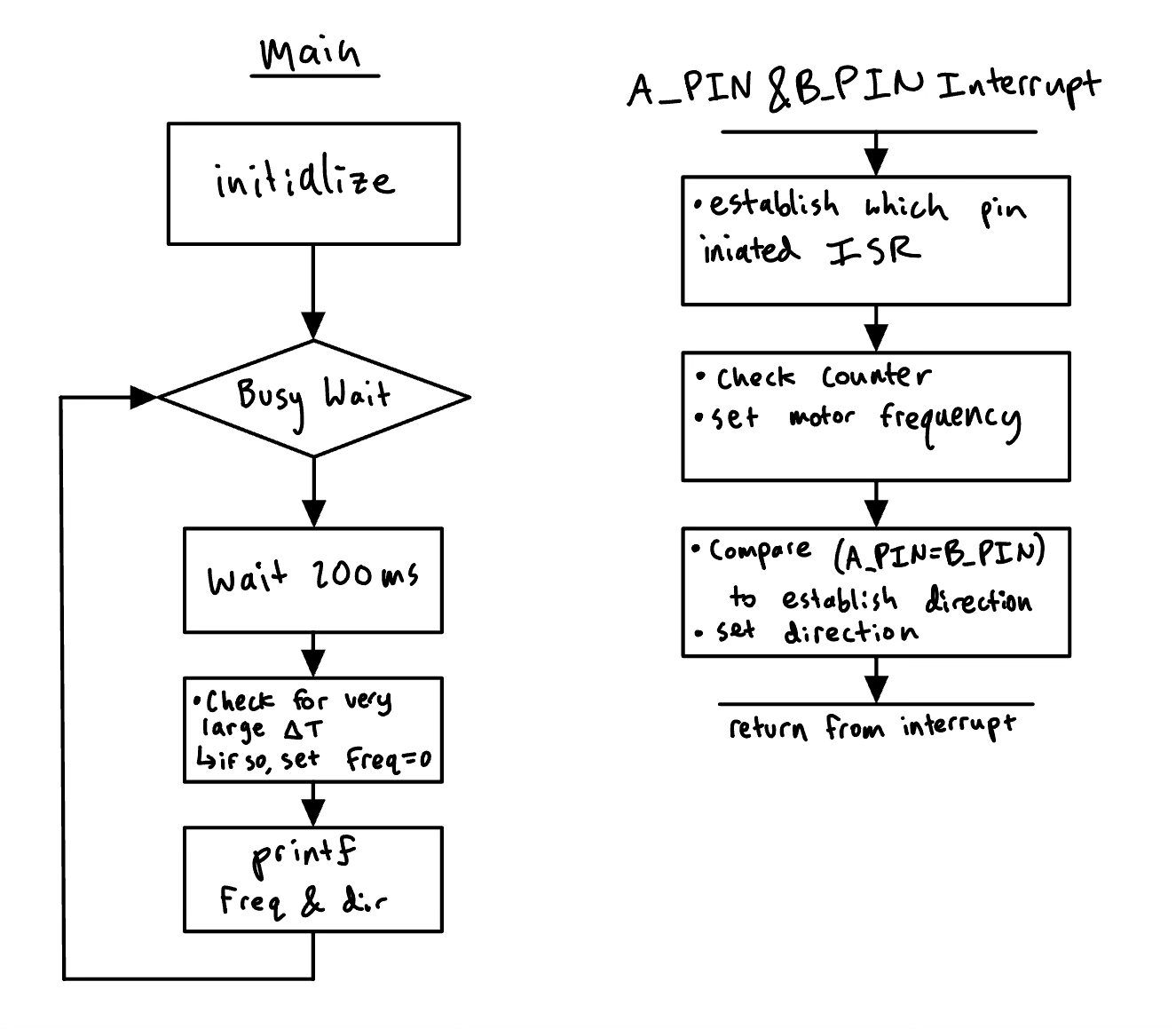

Flow Chart

My program uses an infinity loop consisting of a busy wait that is exited due to interrupts signalling a change in pin A or pin B. Then it does some calculations and measurements before entering the busy state again.

Segger Testing

Before ever flashing the MCU or connecting the motor, I tested my code in Segger Embedded Studio, loaded with drivers and packages for my STM32L432KC MCU. This allowed me to test that my code was working as intended. I looked into the relevant registers ensure that the timers were working as intended.

Frequency and Direction Calculations

Frequency

To measure the frequency I measure the time between two interrupts using a timer. The timer runs off the 80 MHz PLL, with a prescaler of 79 to give a 1 Mhz clock.

\[f_{\text{motor}} = \frac{f_{\text{timer}}}{(\text{\# of cycles between edges}) \times \text{PPR} \times \text{(\# of edges)}}\]

The motor in lab has \(PPR = 408\), and there are 4 edges (rising and falling edges at A and B). Thus we get the following equation:

\[f_{\text{motor}} = \frac{f_{\text{timer}}}{(\text{\# of cycles between edges}) \times 1,632}\]

Technical Documentation:

The code for my project can be found on my github page. Lab5 Github Repository

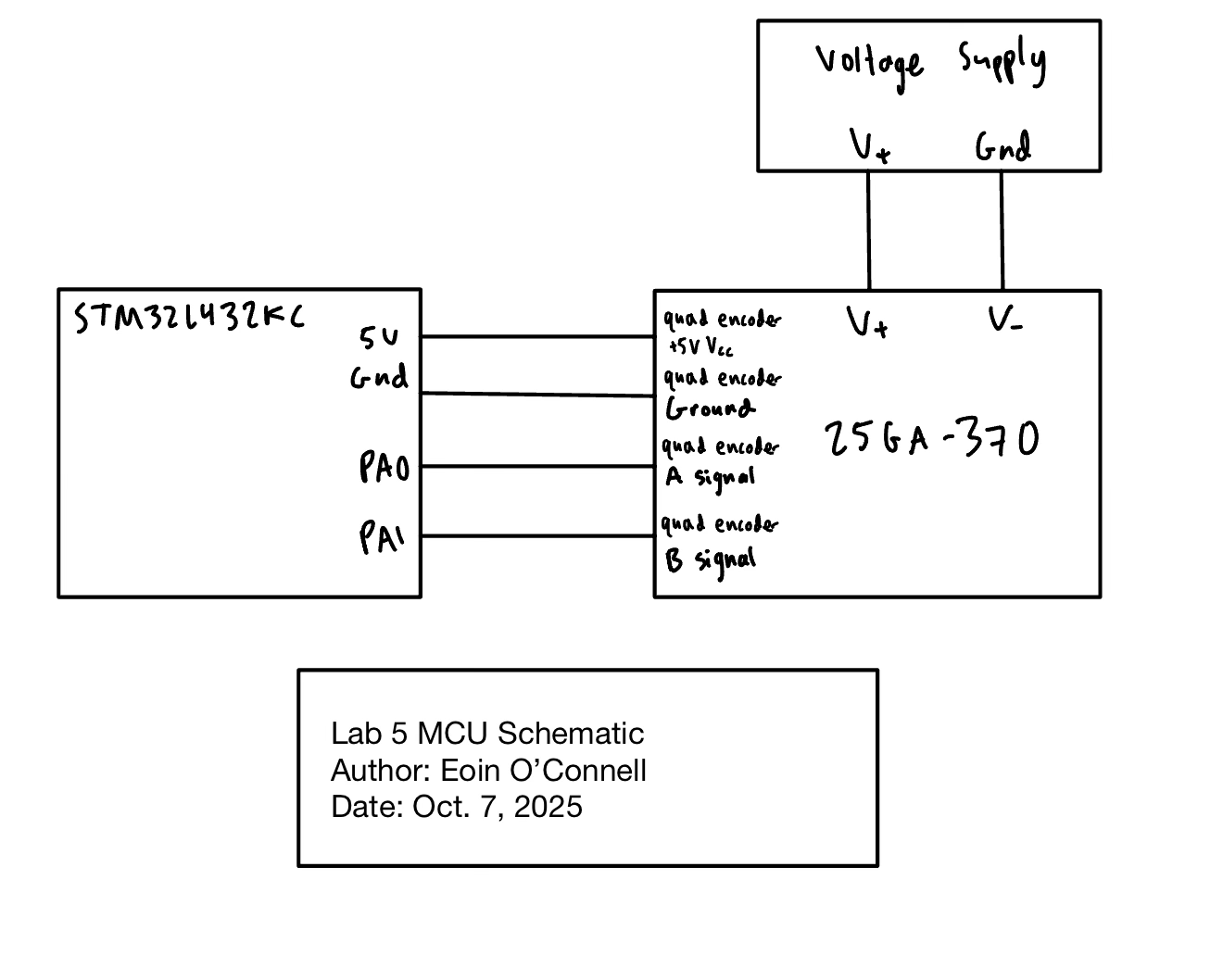

Schematic

Figure 4 shows the physical layout of the design. It shows the microcontroller Pin 6, which has the audio output, first going through a 50 k\(\Omega\) potentiometer to be able to adjust the volume. Then this output goes into the LM386 audio amplifier. By connecting 5V to pin 6, ground to pin 2, and the input to pin 3, and not connection any other pins, we get a gain of 20. This allows us to get a higher voltage output then would have been possible then straight out of the MCU.

Finally, the amplifier output goes to a 8 W, 4 \(\Omega\) speaker.

Results and Discussion

I accomplished all of the perscribed tasks: The microcontroller correctly measures the velocity and direction of the motor. It works at low and high speeds, and outputs 0 frequency when the motor is stopped.

Example Interrupt Based Output

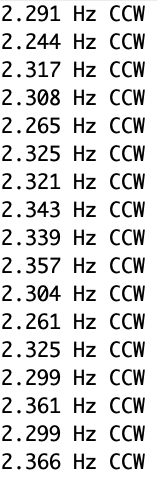

Here is an example output of what the MCU displays when the motor is running at around 10V. From the professor, we expect around 2 RPM at 10V. We can see that we are getting 2.2-2.3 RPM, so our motor is reading values that are reasonably correct. This shows that we are not missing edges and that we are getting accurate readings.

We can see in Figure 5 that the output is not a smooth number as we would expect, there is a lot of data point to data point variation. I wanted to output the most recent data point for maximum resolution, but this introduces a lot of noise. In reality, the motor is not spinning perfectly even, there are points of more and less resistance. When you sample this often through having an interrupt on every edge, some will be slighly shorter or and longer than others. Additionally, this method relies on the points in the motor being even spread out, but there is slight variation which also introduces noise.

In practice, I would introduce a moving average that takes the average \(\Delta T\) from the last N samples to get a smoother measurement, but I didn’t incorporate this to satisfy the requirements of the lab.

Example Polling Based output

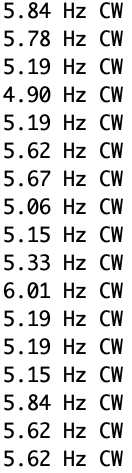

In figure 6, we can see the output of the polling based method, with the motor running at 20V (my maximum). Even at this high speed we do not miss any edges. This shows that both methods are valid for these reasonable speeds.

Conclusion

Lab 5 was pretty difficult for me compared to other labs, due to me having no experience with interrupts, and spending a lot of time just trying to get my first interrupt to register. Once I was able to detect an edge, it was only a few more hours to iron out some bugs with my frequency calculations, and dealing with a stopped motor. Overall, it took about 22 hours in total, including getting the polling method to work and finalize all testing and documentation.

The lab was succesfull as I was able to get everything to work as intended.

AI Prototype Summary

LLM Prompt:

Write me interrupt handlers to interface with a quadrature encoder. I’m using the STM32L432KC, what pins should I connect the encoder to in order to allow it to easily trigger the interrupts?

void Encoder_GPIO_Init(void) {

RCC->AHB2ENR |= RCC_AHB2ENR_GPIOAEN;

GPIOA->MODER &= ~((3 << (0*2)) | (3 << (1*2))); // input mode

// Enable EXTI lines 0 and 1

RCC->APB2ENR |= RCC_APB2ENR_SYSCFGEN;

SYSCFG->EXTICR[0] |= 0x0000; // PA0->EXTI0, PA1->EXTI1

EXTI->IMR1 |= (1 << 0) | (1 << 1);

EXTI->RTSR1 |= (1 << 0) | (1 << 1);

EXTI->FTSR1 |= (1 << 0) | (1 << 1);

NVIC_EnableIRQ(EXTI0_IRQn);

NVIC_EnableIRQ(EXTI1_IRQn);

}

volatile int32_t position = 0;

void EXTI0_IRQHandler(void) {

if (EXTI->PR1 & (1 << 0)) {

EXTI->PR1 |= (1 << 0);

int b = (GPIOA->IDR & (1 << 1)) ? 1 : 0;

position += (b ? -1 : 1);

}

}

void EXTI1_IRQHandler(void) {

if (EXTI->PR1 & (1 << 1)) {

EXTI->PR1 |= (1 << 1);

int a = (GPIOA->IDR & (1 << 0)) ? 1 : 0;

position += (a ? 1 : -1);

}

}I used ChatGPT for my AI reflection, and it used pins A0 and A1, which could be done but they are not pins that have external interfaces on the ribbon cable. Because there are only two wires which directly connect to the motor, I could have connected leads directly from MCU to the motor. Picking these pins makes the code slighly simpler, as it breaks the ISR into 2 different handlers, one for each pin. My handler has to detect which pins caused the issue.

As for the logic of the quadrature, the AI didn’t convert from cycles to time, but this requires external knowledge about the configuration of the timer. It would be relatively simple to convert position to timing.